Due to the sharp increase in the number of refugees, there has been much discussion in recent months about suitable forms of temporary housing . Although decentralized refugee accommodation in apartments is the best prerequisite for sustainable integration in the housing market right from the start, many communities prefer – for the sake of easier administration and support – first of all collective accommodation in communal accommodation. Since in most cases this has to be done under great time pressure, the relevant legal bases have been adapted to the new situation.

the essentials in brief

- Temporary refugee accommodations are classified as special buildings whose standards (in terms of energy, building physics, etc.) deviate from those of conventional housing construction.

- In order to make available space and spatial resources usable quickly, exemptions were created for the development of suitable locations or for the conversion of existing buildings.

- The amendments to the building code have made the construction of refugee accommodation much easier, but the requirements of urban planning and structural quality as well as social and ecological sustainability must not be completely pushed into the background.

Current legislation on refugee accommodation

Unlimited validity

Section 1, paragraph 6, number 13 of the Building Code is valid without a time limit: “The interests of refugees and their accommodation must now be expressly taken into account when drawing up land use plans” and Section 31, paragraph 2, sentence 1, number 1 of the Building Code: “It is expressly provided that the Refugee accommodation is one of the concerns of the common good, which allows an exemption from the determinations of a development plan.

With the Refugee Accommodation Measures Act, which came into force on November 26, 2014, the Building Code (BauGB) was amended and legal simplifications for refugee accommodation were created. Less than a year later, further adjustments were necessary due to the persistently high number of refugees. With effect from October 24, 2015, the Building Code was changed even more extensively as part of the Asylum Procedure Acceleration Act. The majority of the changes were limited to the end of 2019, but some more generally worded paragraphs apply indefinitely.

For example, there is a relaxation of the energy standards for buildings that are only intended to be used for a short period of time.

Framework conditions and building law – relaxed energy standards

exceptions

Exceptions to the law on the consideration of renewable energies are possible for a service life of up to two years. With a maximum service life of five years, new buildings that are intended to be erected repeatedly (e.g. temporary container structures) can be exempted from the requirements of the EnEV if they serve as reception facilities or communal accommodation (§ 25a paragraph 4 EnEV ).

Shared accommodation for refugees is not considered to be a new residential building for permanent living. They are classified as a special building, which in turn is legally defined as a dormitory. As a result, individual conditions can be attached to the approval of a refugee housing complex that differ significantly from the standard of conventional housing construction. These usually relate to the requirements for fire protection, care facilities, the evaluation of energy standards and the construction of car parking spaces. In particular, the relaxation of energy standards, which depends on the service life of the systems, enables faster and easier construction of temporary housing for refugees. In the case of existing buildings, these simplifications relate primarily to the insulation requirements. According to § 25a paragraph 1 EnEV, the thermal insulation standard for necessary construction work on existing buildings used as refugee accommodation is reduced to the minimum thermal insulation.

Planning law – making available space resources usable

Unplanned interiorThe term “unplanned inner area” refers to the areas of the “connectedly built-up districts” according to § 34 Building Code (BauGB) that are not covered by a development plan. Normally, a building project within the interior area is permissible if it fits into the character of the surrounding area in terms of the type and size of the structural use, the type of construction and the area of land to be built over, and the development is secured.

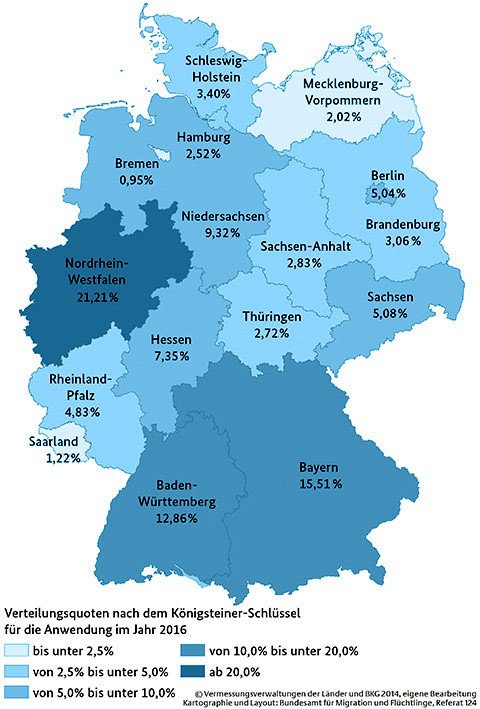

It is well known that the availability of buildable land in inner-city locations is limited. However, to accommodate 80 to 120 people in a residential complex, a plot of land of around 4,000m2 is usually required. In order to be able to set up community accommodation for the corresponding number of people, exception rules were created for the development of locations in the “problem areas” of a city. These include, for example, brownfield sites and commercial areas, but also purely residential areas on the outskirts of the city and the unplanned inner area. This gives the local authorities the opportunity to access selected locations in a relatively short period of time, without having to engage in lengthy B-plan procedures, taking into account the other planning regulations. In the unplanned interior area, for example, all buildings can be converted into refugee accommodation, even if they do not fit into planning law (this applies, for example, to administrative buildings, but also to schools, hospitals or possibly also cultural and retail facilities).

Even in commercial, industrial or special areas, buildings can be converted for a limited period of three years. Under certain conditions, permanent refugee accommodation can also be permitted at suitable locations in commercial areas. In addition, the conversion of existing buildings and the construction of temporary mobile accommodation are favored in the entire outdoor area. Permanent accommodation can also be built on outdoor areas that are directly adjacent to a built-up district. All of these exception rules help to ensure that areas for the creation of refugee accommodation can be accessed more quickly and easily. However, in order to avoid a hasty and unthinking selection of plots, extreme caution is required when applying these exceptions to refugee accommodation.

Procurement law and approval procedures – speed up lengthy processes

Procurement processes are a complex instrument that public clients use to prepare, carry out and accompany their construction contracts. The lengthy process makes it difficult to respond to special requirements, such as the high demand for housing for refugees. Although there are exceptions in public procurement law, these are hardly known. In addition, any deviation from the original course requires political legitimacy. Experts therefore see a need for action here in order to significantly reduce the processing time for a project, which is usually between three and five years. But not only award processes, but also approval procedures are a time-consuming undertaking in the construction industry. Whether you need a building permit for the erection of containers, tents and other forms of refugee accommodation is a question of state law. Depending on the state building regulations, it depends on the one hand on the type of measure and on the other hand on the building law situation. The accommodation of refugees and asylum seekers often, but not always, requires a building permit. If an approval procedure has to be initiated, it should be carried out with priority because of the special public interest.

Costs and quality – look at investments holistically

When assessing the costs of adequate refugee accommodation, the focus must not be solely on the construction costs. [ads-pullquote-left]Good facilities with micro-apartments with private bathrooms and kitchens cost around €25,000 to €30,000 per dorm place, including site development, planning and all applicable fees.[/ads-pullquote-left]In terms of a holistic approach, the necessary financial resources must also be taken into account, which are brought in up to the point at which an asylum seeker is integrated into our society and can contribute something to the gross national product. Higher investments in an integrative and socially sustainable housing supply for refugees are therefore worthwhile due to lower costs and other expenses for subsequent integration efforts. Good facilities with micro-apartments with private bathrooms and kitchens cost around €25,000 to €30,000 per dorm place, including site development, planning and all applicable fees. With a service life of such a system of less than three years, it is also economically viable to rent it. The cost of dismantling and rebuilding is about 30% of the basic investment. Container villages are about a third cheaper than building a high-quality, humane facility that meets the appropriate energy standards. The numerous structural, spatial, social and ecological disadvantages of container villages for the people who are accommodated in them, but also for those who have such a tin landscape placed in front of the window, and for society in general, do not need to be listed separately at this point. But not only for container villages, but in general: If supposedly temporary systems are used for too long, this generates considerable additional costs due to the low building physics standards, for example due to increased heating requirements due to poor insulation or mold growth due to insufficient ventilation.

The amendments to the building code have made it much easier to build refugee accommodation, but the demands on urban planning and structural quality as well as social and ecological sustainability must not be forgotten. In the fourth part of our series of articles on the subject of housing for refugees, you can read what the concrete implementation of collective accommodation for refugees can look like.

Other parts of this series

- Part III – Building for refugees – you must observe these laws when housing refugees